Okay so THIS is my final post. I just wanted to say a quick summary of my thoughts and feelings about the course. Going into the course I wasn’t sure what to expect. I didnt know if we would be intensly studying traditional aboriginal art, and discussing the cosmology in depthly or if it was more exploritory and we could look into different things. It was definately the latter, which is really good in most ways. I really got to follow my mind and just read and write about where my thoughts led me which was great. At some times I felt a bit lost and undirected but then you just find something new and explore that!

After the whole semester I feel much more aware of Indigenous culture around me and much more interested in it. I have a deeper appreciation for aboriginal art now too and I feel familiar with many of the well known Indigenous artists. Which I guess is what this course is about, making us more aware of our traditional Australian culture in hopes that we might grow to appreciate it and support it in any way.

Overall I am glad that I had to do this subject as I think it is really important that we as Australians never forget, or become oblivious to the beautiful indigenous culture that is a part of our past present and future.

For my last blog post I wanted to write about the different regional styles and techniques recognisable in Indigenous art. I think it’s really cool that some people can just look at an indigenous artwork and can tell you what region it’s from and what type of person painted it (male or female, or young or elder). I also think the way they use different symbols to tell stories is really interesting and I would love to be able to read a painting, and understand what’s going on. I’m way more interested in the traditional and historical side of the indigenous culture than the modern urban art and culture, and so I wanted to dedicate my last post to just that!

There is much diversity in the art that has come from the aboriginal art movement over the past 30 years. Particularly in some regions that are still very traditional in culture and language, this art still has a strong resemblance to that of the art that was produced before European contact. Other areas such as the central desert are more modern in their approaches and colours. This is also due to colonization. Since colonization the indigenous culture in some areas of Australia has been wiped out completely. In many coastal areas, the language has been wiped out, and so too has the culture, dance, and art. Regions now have to revive and recover their culture. But in central Australia, and the remote areas, the culture has been kept alive continuously throughout colonization, and their art really shows this. Some of the rock art work in the Kimberly region is an example of the oldest forms of humanity. The art from Arnhemland is very traditional and as I have said the central desert art is more modern. They are all very distinctive very different styles of Aboriginal art. But these too are evolving over time.

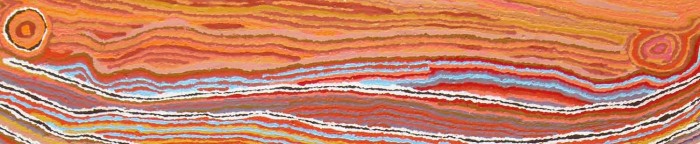

I’ll start of by examining the Central and Western Desert Art. Since the Papunya Tula Wesatern desert dot art movement began in the 1970’s desert art became bigger, brighter and bolder. Acrylic paint usually on large canvas or other materials, and a wide colour palette are features of the central desert art.

Paddy Japaljarri Sims

Paddy Japaljarri Sims

Witi Jukurrpa (Ceremonial Pole Dreaming)

Acrylic on Linen, 122 x 76 cms

2007

Yuendumu school doors are another famous example of some central desert art. In 1983 some senior Walpiri men painted their sacred dreaming designs on the doors of a remote school in Yuendumu (see map). It was a key moment in Audtralia’s art history as it symbolised the Walpiri people’s decision to reveal and try to explain their tjukurrpa (dreaming) to the rest of Australia and the world. Originally 30 doors were painted, to teach the younger generations of aboriginal people of the sacred sites and stories of the dreaming. Over the time they have been used they have grown to tell stories of their own. Graffiti and other wear and tear markings shoiw unique documentation of the hostory of the school as well as stories of friendship and love.

Image above: Door #17 – Ngatijirrikirli (Budgerigar) by Paddy Japaljarri Stewart

Image above: Door #17 – Ngatijirrikirli (Budgerigar) by Paddy Japaljarri Stewart

Moving up to the Kimberly region where colonisation hit hard, art depicts both contemporary and ancient features of landscapes and figurative, abstract and iconographic elements. The art depicts elements of recent history as well as figurative cosmology.They used a restricted colour pallet using natural pigments. One feature of the Kimbery art is that they often painted large blocks of colour outlined with white dots.Jimmy Pike and Rover Thomas who I’ve spoken about before are both from the Kimberly region.

Rover Thomas, Tokyo Crossroads, 1996.

Nancy Nodea, The Kimberlys, 140x100cm

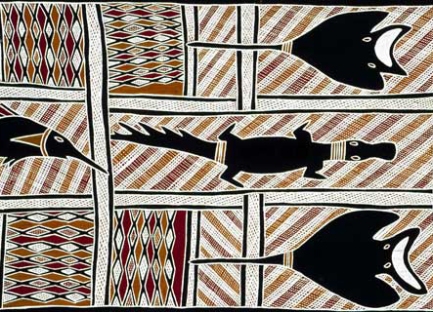

Arnhemland was one of the last regions in Australia to be colonised, and early contact was made with the people of Indonesia. Arnhemland is famous for its x-ray style painting such as skeletal bones or seing the insides of the animal or person. Also the cross hatching using natural ochre on bark, in plain earth tones such as red white and black are prominant features of Arnhemland art.

Arnhemland was one of the last regions in Australia to be colonised, and early contact was made with the people of Indonesia. Arnhemland is famous for its x-ray style painting such as skeletal bones or seing the insides of the animal or person. Also the cross hatching using natural ochre on bark, in plain earth tones such as red white and black are prominant features of Arnhemland art.

Gumatj at Yirrinyina by Madinydjarr Yunupinu 1998

Boyun, Bark Painting, Eucalyptus bark, natural earth pigments, Eastern Arnhemland, Northern Territory, Australia 88cm. x 42cm.

I love the intricate and detailed cross hatching of the Arnhemland paintings and I think they are my favourite.

So this was just a very short introduction into the different regional styles of Indigenous art but I really enjoyed reading and learning about it and I think the bark paintings in particular are extrodinary. I would like to look into it a bit more, who knows maybe I will write about it for my essay… Still undecided.

🙂

Figure 1 http://www.aboriginalartprints.com.au/regions_details.php?region_id=2

Figure 2 http://www.warlu.com/exhibitions/?2007&p=3

Figure 3 http://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/whatson/whattosee/permanent/aacg

Figure 4 http://www.aboriginalartprints.com.au/regions_details.php?region_id=5

Figure 5 http://www.artabase.net/exhibition/1105-mcculloch-s-contemporary-aboriginal-art

Fig 6 http://www.authaboriginalart.com.au/Artist.asp?Artist=Nancy%20Nodea#

Fig 7 http://www.aboriginalartprints.com.au/regions_details.php?region_id=1

Fig 8 http://worldoceanobservatory.org/content/ocean-art-and-literature

This weeks lecture was all about the role of community art centres in Australia and in particular the art centre at Irrunytju (otherwise known as Wingelina). Irrunytju is situated on the tri state border of WA, NT, and SA and is about a 700km drive from Uluru. It is a very dry and remote community with a population of around 180 people.

The Irrunytju people were aware of the success of the Papunya Tula artists and so decided to start an art centre of their own. The aims of the Irrunytju community when establishing the arts centre in 2001, was to:

– support cultural development and inter-generational learning

– to engage in cross cultural advocacy

– to be an economic initiative

It was not just a commercial venture, It was established to contribute to the social, cultural and economic strength of the community. It was responsible for a lot of other things, such as supporting the training and developing of young and emerging artists, supporting cultural maintenance and inter generational learning.

Kuntjil Cooper, an elder and artist of the Irrunytju community articulated these aims when she said (translation)

“When I am gone my grandchildren will be able to understand my culture when they see my paintings. I want my paintings to be treated with respect and I want the right amount of money”

http://www.deutscherandhackett.com/node/17000073/

Kuntjil Cooper (c1920—2010), Untitled, 2003, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 147.0 x 184.0 cm.

http://www.vivienandersongallery.com/galleries.php?gallery_id=20?osCsid=6rtdp1gaekvkivs9pah557kj47

Kunmanara [Wingu] Tingima, Kuru Ala 2006, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 137.5 x 141.0 cm

From 2002- 2006, when the Irrunytju art centre began gaining national and international recognition, the indigenous art market was booming. It was a dominant element of the arts in Australia and is recognized internationally. It was estimated to be worth between 100 and 300 million dollars per year.

Irrunytju was a member od Desart (an advocacy agency for aboriginal art centres in the Western desert), and it was estimated that these art centres generated 12million dolalrs per year in 2005 alone. Of this 7 million was from two of the larger art centres, Papunya Tula and Balgo.

The boom of the market was both a blessing and a curse. The market for art done by the senior artists was booming however there was little interest in the works done by young and emerging artists, which caused some tensions within the community, and created pressure for the senior artists.

These days Irrunytju art is no longer a member of Desart and is privately owned. It is still well established and works from Irrunytju artists can be seen in many private and public collections around Australia and internationally.

I recently came across an article on the ABC news website posted in June 2011 that described Australia’s indigenous youth crime rates at a level of “National crisis”. This really shocked me as I assumed that these rates would be declining with the improvement of the treatment of Indigenous Australians over time. I decided to look into this topic more as I was interested to hear both sides of the story.

This table represents the amounts in 100,000’s of people aged 10-17 incarcerated into juvenile detention centres around Australia not including Tasmania, between 1994 and 2002.

http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/cfi/41-60/cfi060.aspx

The article I mentioned previosly on the ABC news website quotes that Aboriginal youths are 28 times more likely to be detained than non indigenous youths. Why is this? This really provoked some thought in my mind. Are the aboriginal youths really this hostile or does the Australian justice system and police authorities treat the aboriginal youths differently?

To begin my investigation I watched an old episode (1992) of “The first Australians” which was called “Special Treatment”. The episode looks at the special treatment of Indigenous Australians by police and the bad relationship between and defiance of the indigenous youths and the police authority. It discusses the unfair treatment of the youths by the police, in the form of random police searches based on suspicions, and the constant harassing abusing of Aboriginal people. There have been many horrible cases in the past where aboriginal youths have been arrested, beaten, and in some cases even killed for crimes they did not even commit. Unfortunately Aboriginal people have suffered decades of neglect, and I can only imagine the sadness and fear that some aboriginal communities must associate with their local police authority.

Something that really stuck in my mind from this documentary was something a police chief said. He said how Australia’s war was never recognised like the American wars or the Korean wars. Australia’s war was fought by the police, and the aboriginals that fought back were criminalised. The police fought as the military force of imperialism. Australia’s history definitely starts Australia’s police authority and our indigenous population off on a bad note. It affects their relationship negatively to this very day. The country was built on the concept of invasion and colonisation and that will never change and the indigenous Australians will never forget that.

So what can Australia do right now to change this and reconcile, and to repair the relationships between the police authority and the indigenous youths and communities? In the article on the ABC news website it states that the Federal parliamentary committee has made 40 wide ranging recommendations to change these statistics such as better police training, incentives for school attendance and the introduction of mentoring programmes.

Liberal committee member Sharman Stone says mentoring is the way forward.

“If a lot of the Indigenous young people have someone to look up to, whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous, that can help them find their way, their pathway through to life beyond offending,” she said. The article also states that there has been discussion to introduce Indigenous representation in Parliament to give youth a voice. I think there should be a nationwide push to train some aboriginal policemen and women into the force so as there is an equality of race in Australias authoritive system. Police in South Africa imposed strict curfews to all youths at night time. Is Australia at this point? These are all things that Australia could be trying to lower the indigenous youth crime rates.

As I did a bit more research I realised this was a massive topic and I had only discovered the tip of the iceberg. The rise in indigenous crime rates are interrelated with many other factors.

A 2009 NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research study draws many conclusions, such as finding that the rate of indigenous incarceration in NSW (which holds more than one third of the national prisoner population) rose 48% between 2001 and 2008 BUT the rate of indigenous court appearances and the rate of indigenous convictions both fell in the same period. This means that that none of the rise was the result of any change in patterns of indigenous people actually offending. Rather, the entire increase could be explained by the increased use of imprisonment (rather than non-custodial options), longer prison sentences, increased rates of bail refusal and longer periods on remand.

What makes me even sadder is that these negative relationships between Australias police authority and the indigenous community is still a major factor in today’s society. Just the other day I was reading an article in the 22nd August “The Koori Mail”, about a man who had been beaten by the police guards as they were moving him from one cell to another (after being arrested for allegations that were then later dropped). The police officers in question then lied under oath about the situation and are now being investigated by the Police Integrity Commission. The victim states “Hopefully some things will start changing… and no one will have to go through what I have gone through”. The victims fathers stated “I hope this brings about changes in the way police deal with peolple”.

This topic is really controversial and provokes quite a lot of questions. There are always two sides to a story and Australia will hopefully keep working at the reconciliation between Indigenous and non indigenous Australians until there is true equality and peace.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-06-21/indigenous-youth-crime-rates-a-national-crisis/2765676

After watching the film “Ten Canoes” I was intrigued by the process in which the men went through to make the canoes that they sailed down the swamp on. I had heard that the area I’m from, Wentworth NSW, was quite well known for its abundance of tree scars. So I decided to go on a bit of a trek to find some of these dug out trees. I decided to go out to my grandparent’s station, where we drove around the property and stopped at places we thought we might find one. These places were always near water such as a river or a creek. I was happy to find a few different scars, and even some rock shards that I became very curious about.

This tree was my first find. I think this one may have been a canoe as it was quite long.

This scar was the second one I found. I think this may have been a long carry basket for things like long grass. Or it could have been a shield as it looked the right size.

This scar I think is another rounder carry basket, which could have been used to collect things like berries annd many other things.

I did some online research to find out a bit more about these trees. I found out that the Scarred trees are found all over Australia, wherever there are mature native trees, especially box and red gum, and most often occurring along rivers, around lakes and on flood plains. Aboriginal people caused the scars on the trees by removing bark to make many different tools, and with many different purposes. Canoes, carry baskets, shelter and shields are all things that the Indigenous Australians made using these dug outs. The scars, which vary in size, expose the sapwood on the trunk or branch of a tree.

I was guessing what I thought each of the scars I found were from. I think image 1 would have been a canoe, image 2 a longer carrying basket for things like long grass reeds to make string, and image 3 and shorter rounder carry basket, for berries or something.

To remove bark, the Aboriginal people cut an outline of the shape they wanted using stone axes or, (once Europeans had arrived) steel axes. The bark was then levered off. Sometimes the axe marks made by Aboriginal people are still visible on the sapwood of the tree, but usually the marks will be hidden because the bark has grown back. The amount of bark regrowth may help you tell the age of the scar. Sometimes, if the scar is very old, it will be completely covered by regrowth. Trees with these cutouts usually date at over 200 years old.

I also found a few sites of different rock shards, which I found very interesting.

These photographs are my property they belong to me and may not be reproduced in any way without my permission

This film is based in the swamplands of Arnhem land thousands of years ago. It involves a story within a story within a story. The narrator’s voice, and the zooming, and panning shots of the brightly coloured swamp landscapes distinguish the first story. The second story is filmed in black and white, and involves ten indigenous men building a canoe each to go out on the swamps and hunt for goose eggs. The youngest of the group is in love with his brothers wife and so the elder of the group tells of a story that happened many more thousands of years earlier before white settlers came to Australia. The directors show this story in colour.

The film was narrated in a humourous yet informative way, by the actor David Gulpili, as he was the one who instigated that someone make a film about the traditional people on his traditional land. Rolf De Heer responded with this film.

The narration was very humorous and so was some of the camera shots and the way the characters interacted with each other and the camera. I liked the shots where the narrator would introduce a character and the camera would flick to a direct portrait shot of their head where they would all react a different way. Some of the ladies laugh, some of the men would just stare. These shots were almost anthropological and reminded me of the photographs I saw in the Museum taken by Donald Thomson.

These were taken at the Museum of South Australia on North terrace.

Camera shots like this one seem anthropological.

I also loved the humourous way in which they woud act out different scenarios that could have happened such as when Nowalingu had gone missing and the men were all deliberating what happened to her.

This film is full of really interesting and funny characters such as the proud warrior Ridjimirali, the wise elder Minygululu telling the story to Dayindi and of course Birrin Birrin the honey eater. The film also has plenty of drama with themes of sourcery, wife stealing and tribal revenge.

This film was a great display of ancient indigenous aboriginal culture and way of life. I love the fact it was mostly spoken in their tribes native tounge as it really creates authenticity. It was a very entertaining film and gave a lot of insight into their ancient culture and spiritual practices.

I really appreciate artists that take something old, and traditional and re-interpret it into something really new and truly unique, and Jimmy Pike’s psychedelic aboriginal Art certainly fits this description. Some words that I would use to describe Pike’s work include flamboyant, psychedelic, bold, and striking. His work is characterized by bold shapes and lines in brightly contrasting colours that draw your eye in and move it around the artwork.

Jimmy story is quite amazing, growing up in a very traditional indigenous community on the edge of the sandy desert of north Western Australia. He was born into the Walmajarri people at Japinkga in 1940 and was taught to hunt and gather food the traditional way, using tools and hands only. He and his family continuously travelled by foot around the dry land to different water sources, and it is evident in his work that the symbols and imagery is inspired by this. Pike had his first meeting with a white man at age thirteen when he began work at Old Cherrabon station as a stockman. The manager of the station gave him the name jimmy Pike after the famous jockey that rode Phar lap.

When Pike was introduced to alcohol it got him into some trouble with the law in which he was sentenced to some years in a Fremantle prison. It was around 1980 while Pike was in prison that he discovered his talents and love of painting. He learned how to use acrylic paints and make lino prints. He was also in prison when he met Pat Lowe – a practicing psychologist, who helped him to sell his artworks and turn his paintings into fabric and other goods. Pat and Jimmy travelled the world together making and selling his artworks in places such as the United Kingdom, Italy, China, the Philippines, and many more.

I really like Jimmy Pike’s artworks and would love to own some of his pieces one day. I think his style is really unique and eye catching, and the story behind them is intriguing as well.

Jila II, Lightweight Cotton (multicolour)

Nookamka – Lake Bonney, 2007, watercolour and coloured pencils on ink on canvas, 74.2 x 203.0 cm

Nici Cumpston was born in 1963 in the Barkindji area – which is where I am from!!. This made me interested in her right from the start as I could relate to the areas she mentioned and other things she spoke about.

Nici studied photography and then got her first job in the photography department at the South Australian police department. This influenced her later work, as her photographs take on a very ‘investigative’ and ‘documentary’ approach.

I really like the way that Nici approaches her photography of these sacred aboriginal sites, and i really like the way she talked about it. She emphasised that she likes to look, listen and feel when she is walking around the outback. She then thinks and wonders about the past interactions that occurred on the land. She really appreciates the fact that we weren’t the first people on Australian land, and that if you actually take the time to look, there is alot of evidence left on the trees, the rocks, and in other object such as rock shards, of the past inhabitants.

A fascinating part of Nici’s technique is that she hand colours her photographs with watercolours, a technique which she learnt from lecturer and mentor Kate Breaky, who also attended UniSA.

Nici’s works have a distinct haunting beauty to them. Her current work relates to the poor state of the Murray Darling rivers, and to the dying Lake Bonney. She seems to be able to portray beauty in the dead, dying and distorted tree trunks left behind from receding water levels and intoxication from saline.

Nici Cumpston

Keeper 2008

inkjet print on Hahnemuhle paper

140 x 60 cm

This piece is part of a series of three called Keeper. It is a striking image of a hollowed out tree that was used by indigenous aboriginals as a birthing place. Coming from the Brakindji area Nici is very connected to the rivers and recognises the facts that these places bear witness to indigenous Aboriginal stories, heritage and habitation.

Image from http://www.smh.com.au/news/biennale/not-happy-australia/2008/06/23/1214073123939.html

Vernon Ah Kee

Vernon Ah Kee is an aboriginal/ chinese man, born in Innisfail Queensland. He studied a bachelor of arts and completed an honours degree in Fine arts at Griffith University in Brisbane. When he was younger he knew no artists, and trawled through any artistic books he could find that could help him learn how to draw. After completing his university and honours degree he went on to teach for five years. However it is the large charcoal, pencil and acrylic portraits (picturted below), some up to 3m tall, and his political text based works that have made his name stand out over the past eight years.

Ah Kee creates massive and sometimes confronting portraits of family members creating an idea of what it means to be aboriginal and what it means to be human. He syays “My portraits are beautiful because I want the subject, Aboriginality, to be a beautiful thing”.

Ah Kee is also part of the Proppa Now group and is one of the most political aboriginal artists of his time.

His 2002 collection titled “If I was White” critiques Australian pop culture, in particular the separations and segrergations that still occur and divide the Black/White Australians.

image from http://www.ferrabyling.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/If-I-was-white2.jpg

In an article in ‘The Australian’ titled “The Face: Vernon Ah Kee”, Ah Kee touches on the topic of Aboriginal Art exploitation, stating that the artists do not understand their role. He states

“Aboriginal art is a white construct” and that “Communities up north are poverty stricken and in upheaval, but looking at the art that comes out of those areas, the galleries in Melbourne and Sydney would have you believe their lives are wonderful; not just wonderful but ideal…”

One of Ah Kee’s more recent exhibitions “Cantchant” first released in 2007 is a really interesting representation of the surf culture of Australia and the Australian Beach, which to white Australians is a typical iconic place that represents everyday practiuces of ‘Australians’. Ah kee challenges the white Aussie ownership of the beach by visually representing the lack of Aboriginal sovereignty. The surfboards painted like shields with aboriginal art and colours of the aboriginal flag look almost odd yet depict a sense of resistance nto the white Australians. On the other sides of the painted surfboards, the eyes of Aboriginal portraits glare at passers by silently as if to siginify their unwanted prescence.

The Tightly spaced text on the walls speaks political truths, and adds to the exhibitions overall message.

” We are the first people, we have to tolerate you, we are not your other, you are dangerous people, and your duty is to accept the truth”

“We grew here”

“Your duty is to accept me, My duty is to tolerate you”

IMage from http://www.ima.org.au/pages/.exhibits/cantchant88.php

Image from http://corycooperindigenousdiary.wordpress.com/2010/10/23/vernon-ah-kee-cant-chant/

This exhibition really caught my eye. I think the idea of an aboriginal surfer is really odd, but it shouldnt be. You just dont see many aboriginal people surfing, thats why this exhibition is such a great juxtaposition. It shouldnt be so odd, as the Aboriginies were first on the Australian land including its beautiful beaches, so why then have they been pushed inland, away from the beach lifestyle and cultre?

I would like to see the exhibition in person as there are some videos that go with it of some aboriginal men taking these painted boards out to a beach in Queensland and getting some weird looks. I admire Ah Kee’s work and I think he does a great job at sending a message to the viewer, and really makes them think about aboriginality, and there true existance in a white Australia.

‘Roads Cross’ Contemporary Directions in Australian Art

Rover Thomas (Joolama), Tokyo Crossroads, 1994, Etching, edition no: 10/20, 80 x 60 cm.

This artwork is just one of a series by Rover Thomas, one of these images (very similar to this one) provided the exhibitions title and the first visual for the exhibition.

For our tutorial this week we visited the Flinders gallery on North Terrace under the state Library. The exhibition showing there at the moment is called “Roads Cross”. It is a very interesting and slightly contoversial exhibition as it is a series of appropraitions of Indigenous aboriginal artworks done by 16 non indigenous artists in the past 15 years. It aims at creating a snapshot of where things are at in this day in respect of aboriginal and non aboriginal artists collaborating and the appropriation of Indidgenous art. Few of the pieces in the exhibition were co-created with the help of an indigenous artist but other than this they are all ultimately by non indigenous artists. Each artwork has a different story behind it. Some of the non indigenous artists went and lived in the indigenous community and were taught by the indigenous elders whereas some just appropriated out of images they had seen in books or exhibitions. Some of the artists had full permission to appropriate while others did not. This is where the controversy and blurred lines come into the issue.

One question commonly asked about the exhibition is who is benefittitng from the collaboration? Are these appropraitions further taking away and disrespecting the culture or is it a further reconcilliation between the cultures? Another question that helps to answer these previous ones are Who is driving the collaboration? If the power dynamic between the collaboration is uneven, and the reasons or purposes behind the collaboration are not clear to the Indigenous aboriginals, then this is a case of the collaboration only beneffitting the non indigenous artist.

Something I found really interesting about the exhibition was that there were no examples of indigenous artists appropraiting non indigenous artists. Richard Bell sprang to mind as soon as heard the word appropriation. He appropraites famous artists such as Roy Lichenstein and Jackson Pollock in many of his works. Is this not the same principle? Some would say it isn’t as the indigenous people have a spiritual connection with their artworks, but whos to say these artists don’t either?

Another thing I found really interesting was when the gallery attendant said about how Rex Battarbee taught the famous Albert Namatjira how to paint, and then in this exhibition someone had appropriated Albert Namatjira’s wortk. It is an ironic cycle.

Overall I enjoyed this gallery visit, and its was really interesting to see a different perspective on indigenous art coming from non indigenous artists. I beleive if the collaboration is of equal power dynamic and the artist has permission then its certainly okay and shows a further reconcilliation between indigenous and non indigenous people.